The Shifting Tide: A panel presentation with Eco-Age. 08/09/2022

This brief presentation was part of a virtual session on The Great Greenwashing Machine, an update on the latest in greenwashing held by Eco-Age, in partnership with the Geneva Institute for Business and Human Rights.

As my co-author Professor Baumann Pauly has just observed, green claims, at least in the apparel sector, have become separated from the true meaning of sustainability - that of climate change with climate justice. Indeed, in direct violation of the global north’s commitments to the UN SDGs, it is now pretty standard to equate ‘green’ and ‘sustainable' with environmental impact and to ignore socio-economic impact completely. The injustice inherent in this approach aside, how accurate are the environmental claims that many currently make in the apparel sector, and who is checking?

The most common means of substantiating environmental claims is through life cycle analysis or LCAs. Doro and I have recently published a white paper, that is available, open source on the website of the Geneva Center for Business and Human Rights: The Rise of Life Cycle Analysis and the Fall of Sustainability. This is a screenshot of the cover. I only have a few minutes to cover the topic today, so please read the paper for a more complete picture.

https://gcbhr.org/insights/2022/07/the-rise-of-life-cycle-analysis-and-the-fall-of-sustainability-illustrations-from-the-apparel-and-leather-sector

In a nutshell, the problem is that unlike financial accounting, sustainability accounting does not have a framework that everyone adheres to and for which outcomes are audited. There is no established LCA model that everyone in the apparel sector uses. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has guidelines, and many commercial LCAs in particular, will tell you that they were produced to ISO standards, but an array of different methodologies and boundaries are ISO compliant, whilst a standard for data collection - and data is the most crucial variable in every LCA model - does not appear to exist. There is, moreover, no real oversight of any of it.

LCAs are not absolute. They are not a sausage machine, or a cookie cutter. From any given set of raw data, there is no single, unique value that will automatically be generated for greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption, eutrophication, etc. and, as I will show you in a minute, vastly different purported impacts can be obtained from exactly the same data, by using different models, methodologies, and/or boundaries.

ISO 14021:2016 in fact states that consumer facing claims cannot be made if the verification depends on confidential business information. But nobody adheres to this. From the Higg MSI, to brand and manufacturer websites, claims are made based on LCAs that are not available to the general public. And as we shall see, this is highly problematic.

As David Perry has just pointed out, the CMA has a Green Claims Code which requires such claims, and I quote: “6. Be substantiated: Businesses should be able to back up their claims with robust, credible and up to date evidence.”

But what constitutes ‘robust’, ‘credible’, and ‘up to date’ evidence?

Let’s start with the final point:

1.What constitutes ‘up to date’ ?

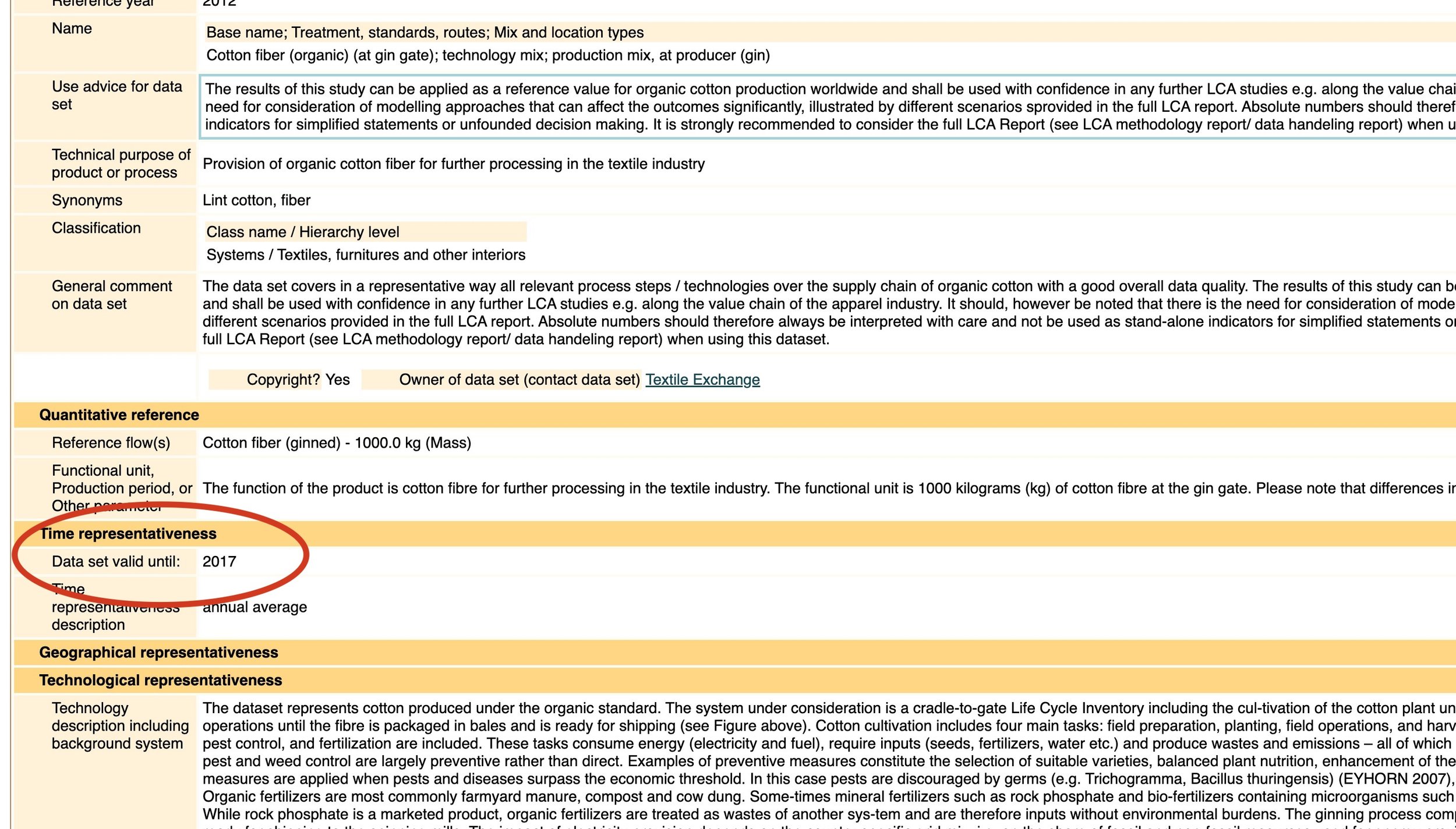

If you go to the Higg portal, and click on the data link for the MSI for cotton fiber organic, this is a screenshot of what you will see. Sphera Gabi, which is the source, states that the LCA underpinning the MSI ceased to be valid in 2017.

https://portal.higg.org/5f29070fddc3b80009bb60e3/product-tools/msi-v2/example-materials?initialSearch=Cotton%20fabric

Yet 5 years later, in 2022, the MSI is still using this LCA to claim that organic cotton consumes 92% less water and emits 45% less GHGs in cultivation than conventional cotton production. That the LCA does not in fact substantiate either of these claims is another matter. Here, we are looking at what constitutes ‘up to date’. Sphera, formerly PE Consulting, actually wrote that referenced LCA. They say it is no longer valid. . Higg, and indeed Zalando, who used precisely this claim in their July 16, 2021, submission to the CMA itself, and (as the screenshot shows) are using the 90% less water claim on their UK website, right now, both obviously disagree. Who is correct?

Screenshot taken 07/09/2022

2. What constitutes ‘credible’?

In their submission to the CMA (as the screenshot below shows), Zalando refers to the Higg MSI as “the apparel industry’s most trusted tool to measure and score the environmental impact of materials.”

But since June 16, 2021, a complaint from the International Sericulture Commission, about the way in which the MSI calculates its scores, has been included in the US Federal Trade Commission's secure online database. This is a screenshot of the FTC letter announcing that inclusion. It states that the FTC database, and I quote:

“is used by thousands of civil and criminal law enforcement authorities worldwide. This database enables law enforcement agencies to identify questionable business practices that may lead to investigations and prosecutions.”

Email from Dileep Kumar Wed, Jun 16, 2021

And finally,

3. What constitutes ‘robust’?

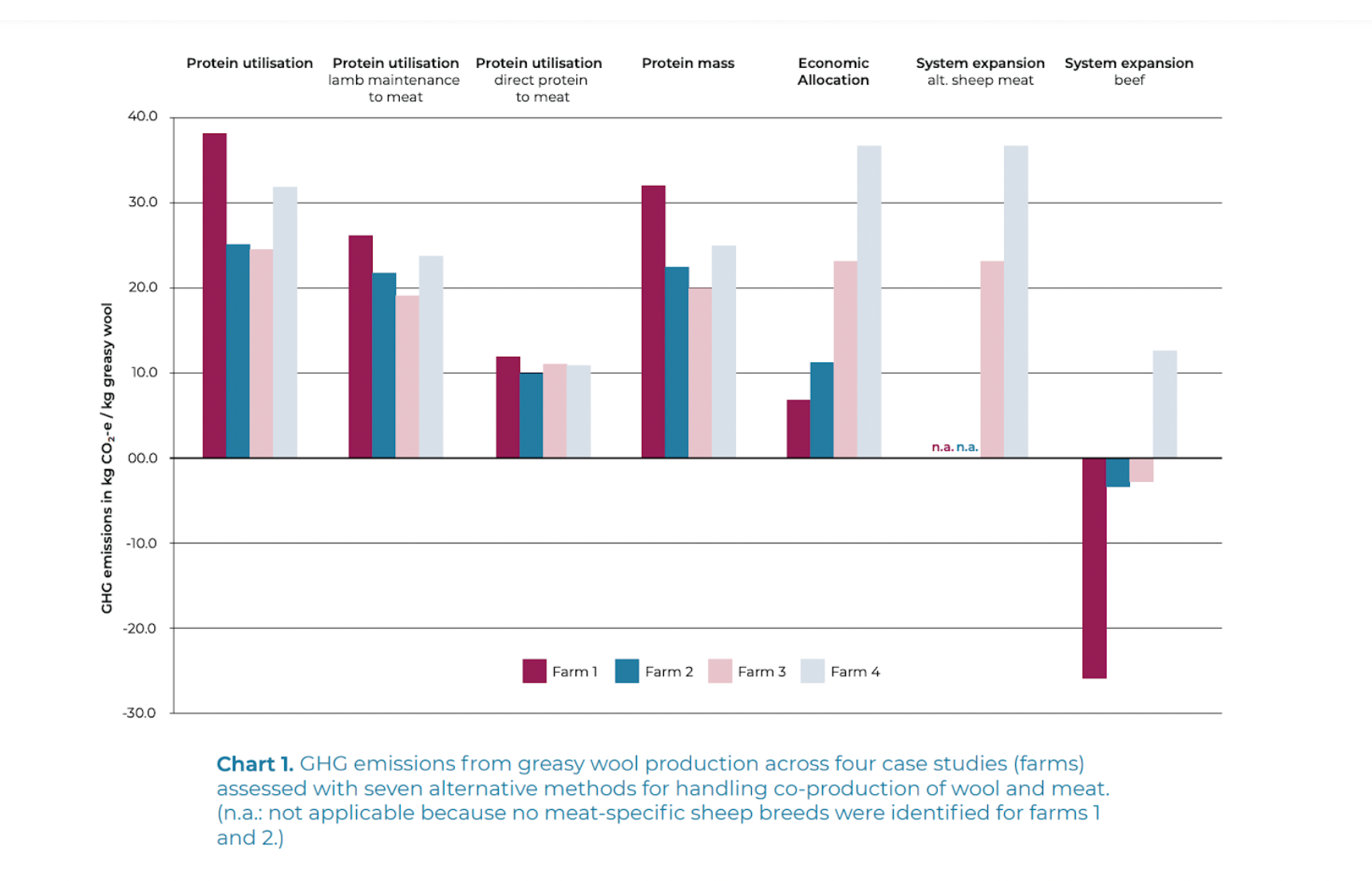

The screenshot that you see now comes from the white paper that I mentioned at the beginning of this presentation.

https://gcbhr.org/backoffice/resources/the-rise-of-lcas-and-the-fall-of-sustainability.pdf

We adapted this chart from a wool LCA comparing the Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHGs) of four different sheep farms by applying seven different methods of allocation between wool and meat. All 7 of these methods are acceptable under ISO standards, so this could, to some extent, apply to any fiber.

Look at the red bar. This represents the GHG impact of one farm - Farm One. If, using system expansion, that farm claimed that their ghg impact was negative and that buying their greasy wool actually reduces climate change to the tune of almost 30 kgs of CO2e per kilo of wool, would their claim be robust? Or if an index such as those owned by Sphera or Quantis used protein utilization to claim that Farm One’s wool had a ghg impact of almost 40 kgs of CO2e per kilo of wool, would their claim be robust?

Our white paper concludes that legislators cannot rely on commercial databases and commercial LCA providers to inform legislation. We strongly recommend that brands not be allowed to make any consumer facing comparative assertions until the yawning data gap that we discuss in our paper is filled, and agreement on aligned methodologies, reached. In the interim, brands that really want to reduce impact could offer more equitable contracts, and make long term bankable, purchasing commitments. They could source yarn and fabric from France due to the low carbon intensity of that country’s grid mix, and the fact that the minimum wage is a living wage, or from a solar powered Bangladeshi mill minimizing ghg emissions in spinning, weaving, etc. Such moves would cost more, but their positive impact would be real and measurable.

And please note, we are not the only people taking this position. Going forward, brands are going to have to reckon not just with the CMA or the NCA - the Norwegian Consumer Authority. A class action suit against H&M, for making misleading sustainability claims about its products, was filed in the state of New York, in July. As to what all this means for brands, I quote leading authority in fashion law - Alan Behr:

“The key learning is: unless you and you alone really can be sure that what you are doing is better for the environment... it is far too early in all this to start boasting about it in your marketing materials.”

I suggest that everyone should follow his advice.